Can Street Art Help Restore One of Hanoi’s Poorest Communities?- Urbanist

Can street art lead to urban restoration? Or is it wilful gentrification? In February 2020, the Phuc Tan Public Art Project officially opened — the work on display offers engaging art and stirs up intriguing questions in equal measure.

Sixteen Vietnamese and international artists set up the ambitious installation over a two-month period in Hanoi’s bleak midwinter, and all on a next-to-zero budget. Curated by Nguyen The Son, an artist and lecturer at Vietnam Fine Arts University, the project follows on from the illusory trompe-l’œil murals on Hanoi’s railway arches, also organized by The Son, that’s now firmly imprinted in travelogues globally.

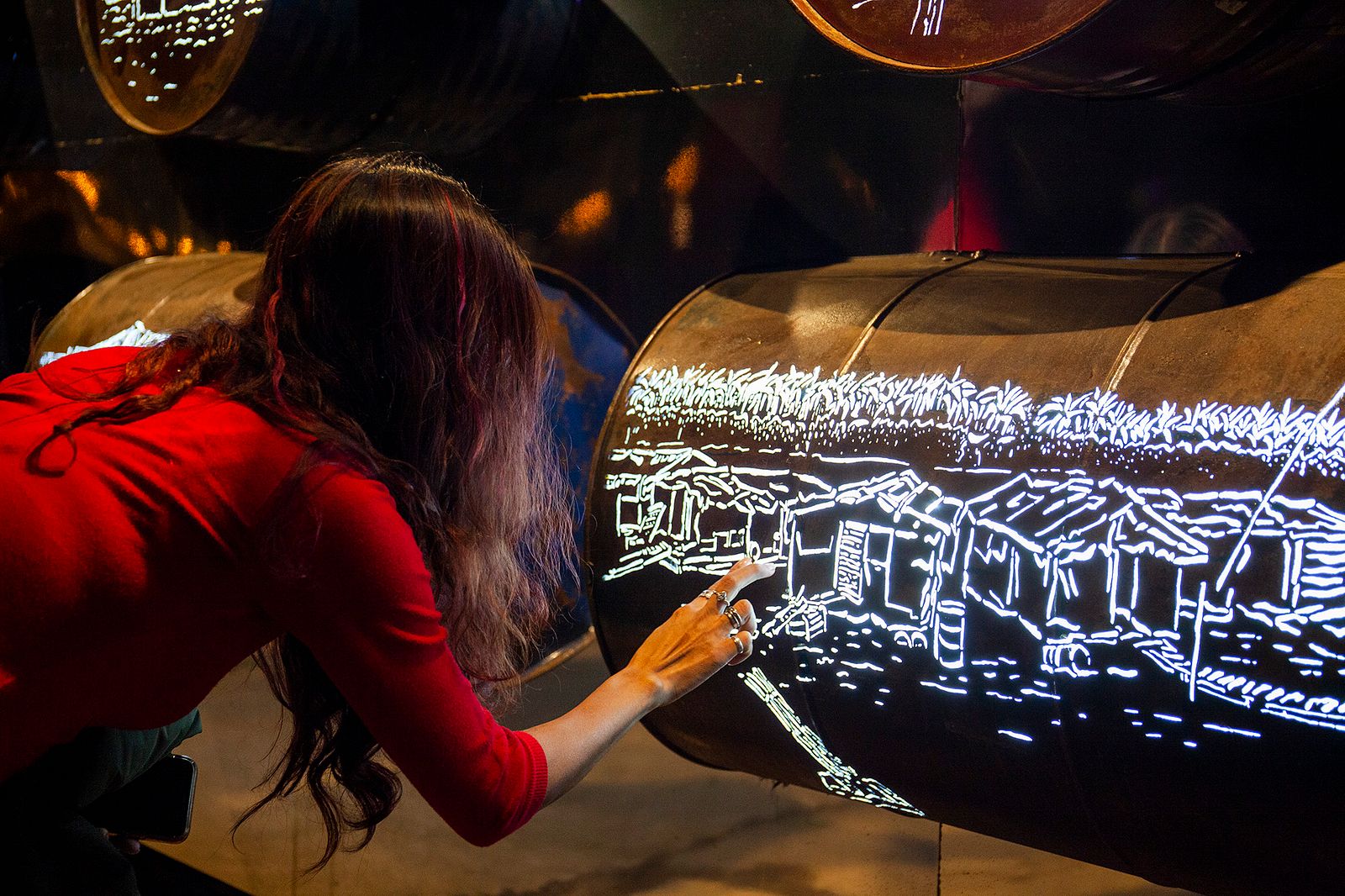

The artwork covers over 200 meters of wall space beginning at the foot of Long Bien Bridge and reaching south towards Chuong Duong Bridge. The display is easy to access through Phuc Tan’s alleyways, and the artists also integrated lighting into the installations, making a nocturnal visit (from 6 to 10pm) an absorbing addition to Hanoi’s map of available cultural activities.

‘Rotation’ by Trinh Minh Tien.

The full list of Vietnam-based artists involved in the project is impressive: Nguyen The Son, Can Van An, Pham Khac Quang, George Burchett, Vuong Van Thao, Trinh Minh Tien, Le Dang Ninh, Nguyen Hoai Giang, Nguyen Tran Uu Dam, Nguyen Xuan Lam, Nguyen Ngoc Lam, Diego Cortiza, Tran Hau Yen The, Vu Xuan Dong, Nguyen Duc Phuong, and Tran Tuan.

With each piece presenting a chosen aspect of the area’s history and using at least one element of recycled materials, the display is unique to the city. Themes vary enormously: some artists explore the history of rising river levels, others portray imagery of Long Bien Bridge, contemporary social media practices, or the nation’s dying blacksmith trade.

Artists also added layers of eco-friendly messaging. Some do this quite obviously, such as Australian George Burchett plastering slogans that read “Make Hanoi Clean and Green,” and others more subtly, such as Pham Khac Quang using found plastic bags to color the background of his piece ‘Xam on the trams.’ Of particular note is Vu Xuan Dong’s impressive installation ‘Boats.’ Created using an ensemble of over 10,000 plastic bottles he collected over a three-month period — with the help of local schools and groups — the artwork is simultaneously an ode to the area’s trading past and a plea for a more environmentally respectful future.

‘Boats’ by Vu Xuan Dong.

The Son hopes these messages will influence passersby directly, dissuading them from using the surrounding area as a communal rubbish dump.

“[We bring] public art and let the people change their minds about keeping the environment clean… Slowly, the local government and people that live here are cooperating in making… it much cleaner than before. So I think it’s good for them and of course it’s good for changing the environment and slowly changing the function of this area,” he says.

“We try our best to make a good example of public art. You can see here it’s a good reaction and interaction with the community, the most important is that the community that lives here and that surrounds the area can benefit and that it is a part of their life,” he adds.

‘The Wall of Fame’ by Tran Hau Yen The.

Hanoi has a very specific relationship between art and public space, and this new project illustrates a form of urban development that will surely influence many similar projects in the future. As Phuc Tan’s restoration process begins, I wonder if the Hanoi context adds to the wider narrative of state-supported public art projects, which are often highly frowned upon in other countries for their detrimental effects on local communities. Rising rent prices and residents being pushed into resettling in other affordable — albeit often of poorer quality — living areas are often cited as consequences of gentrification.

The Phuc Tan neighborhood, part of Hoan Kiem District, is wedged in between Hanoi’s historic Old Quarter and the Red River. In the distant past, the wharf here was the main transition point for goods being brought to the city center. Back then, the river flooded each year, with water rising tens of meters high and washing away anything in its path. Damage mitigation remains a not-so-distant memory for members of older generations in the area.

When I ventured to Phuc Tan to meet The Son one sunny Monday afternoon, I was met with a plethora of kids engaging in activities, tea-stall bickering and some conspicuous gambling. It all seemed pleasant in the light of day, though it seems this is not always the case. “When I show the project in the media, everyone asks where it is! Ninety-nine percent of people that know me don’t know the area,” The Son says.

On the left, ‘Xam on the Trams’ by Pham Khac Quang; on right, ‘Floating Houses’ by Le Dang Ninh.

The area, though referred to by some as a storage area, slum, or backend of the city, is actually little known to many Hanoians. Its end-of-the-road location has also led it to be easily overlooked.

“This area is the storage of the city. The people that live far away come here to throw trash” The Son says. “This area is very dark at night, even before I carry out the project I never come at night. I feel it’s not safe and the people in this area are quite complicated.”

The Son, having already successfully carried out the Phung Hung Street mural project years earlier, was approached directly by members of the district’s People’s Committee. Not long ago, the street was in poor shape. It was being used as a parking spot for taxis, and many in the area had taken to using the walls as a toilet. Nothing deters public urination like a happy tourist snapping holiday pics. Since the area was given a facelift by The Son, the stretch of road has become a pleasant hangout for locals and visitors alike.

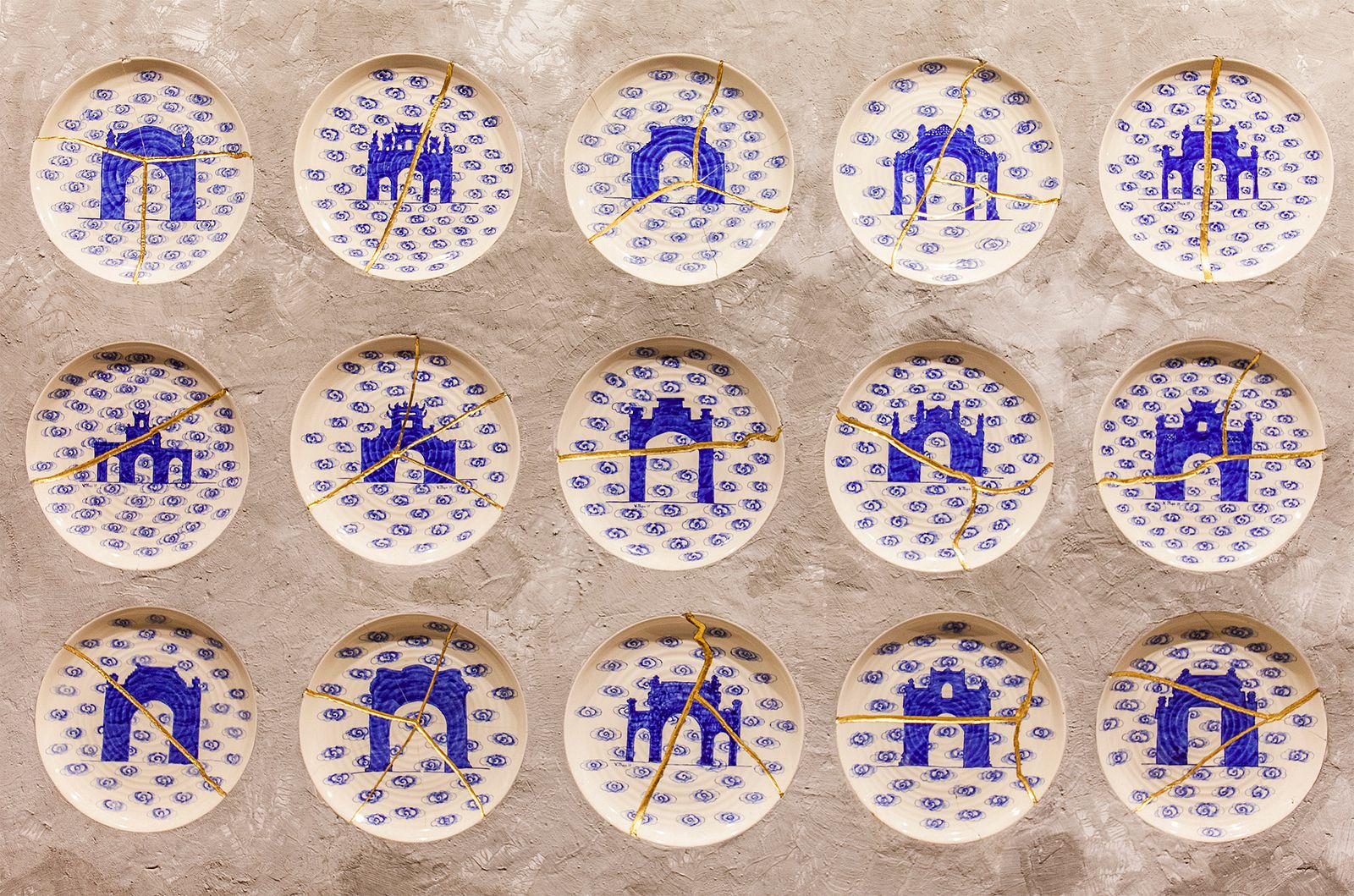

‘Ceramic History’ by Vuong Van Thao.

The Phuc Tan initiative comes from a different place. According to The Son, its first priority is to protect the wall from being knocked down by locals wanting to extend their property. Previously, there were few reasons not to do so. The second focus is for those living here to reap multiple projected economic benefits as a direct result of bringing public art to the community. The beautification of the space is set to attract numerous visitors, and that, in turn, will spill over into more income-generating opportunities.

And so The Son’s research began, as it often does in Hanoi, with drinking tea at outdoor stalls. He was quickly made aware that the locals didn’t care for art and were much more interested in the district paying for a new road. Unfortunately for them, budget restrictions meant The Son was promised support only in seeking funding or through the offering of connections with local companies that may donate to the project.

The Son approached the community in order to seek their approval. Group meetings were organized by local leaders and over a hundred families were told of the potential impact of the project, which is actually the first step in a much larger plan to turn the riverside into a flower park and public promenade. With more visitors, The Son explained, the locals would have a larger range of income possibilities, cafes and homestays would bring in more revenue, and eventually, the district would invest in more stable infrastructure. After seeing The Son’s rendered 3D images, the families saw the future beauty of their neighborhood and grew excited. In a matter of weeks, the volunteer artists had completed their installations.

‘Overall Reflection’ by Can Van An.

The project’s unveiling last month was celebrated by all involved parties, from the local community to the People’s Committee, the wider public and artists alike. Rare are occasions where such groups stand together to support what is, essentially, an example of gentrification. At the hopeful beginning of the process, I wonder how exactly the project will help clean-up Hanoi’s riverside.

As I finished my walk along the wall, the works came to life thanks to illuminating lights each artist used to make their piece visible in the evening. The area’s trash is somehow less noticeable at dusk, and the view of Long Bien Bridge is strangely silent, even during rush hour.

With a well-trained squint, you can nearly imagine the polished park and European waterfront the government is hoping for. But it begs the question: who will share that view? Prevailing faith in humanity hopes the locals are the primary benefactors of the improved environment but, in the end, will that be the case? Once the riverside more closely resembles a European promenade, will the community still have the means to afford living there?